Worship at the Speed of Sound

- WORSHIP AT THE SPEED OF SOUND TRENDS:

- YES. There is an indisputable and ongoing trend for songs to rise, peak, and fall with greater velocity.

- YES. The gap between song publication (i.e. release) and emergence (i.e. appearance) in churches is lessening.

- YES. More popular songs are entering nearer the top of the list, rather than making a slow rise/ascent.

Last year we were approached by Dr. Mike Tapper to publish a very important study, “Worship at the Speed of Sound,” they (Marc Jolicoeur, Lisa Corbin, Charldon Dennis and Andrea Hunter) had completed regarding the accelerating pace of creation, distribution, ascent & decline in the life of congregational worship songs. We’re honored to share this very important study with you both in full text and digitally. We encourage you to comment your thoughts about their findings below. You can also read our response to the study here.

Read the digital version of the study or the full text below:

Download the digital version of the study here

The differences between a song like “Shine Jesus Shine” (1987) and “Who You Say I Am” (2017) are not just a matter of the date of composition, content, or musical style. These songs have lived very different lives.

The Challenge

You’re planning next weekend’s service and wrestling over the right songs for your congregation. There’s that new, upbeat song, but you’ve done it four times in the last six weeks, and you don’t want to kill it. You received emails last week from people in your church suggesting the “perfect” song, but none of them match the vision for your pastor’s hoped-for response to the sermon. You’ve already done “I Surrender All” a few times in the last six months and you’re hoping for something a little more contemporary. Yet, all the newer songs you can think of are neither high-rotation enough nor new enough to be really, new. So, you turn to the top song lists to see if what’s trending might work and you find a relatively different list than the last time you checked. Frankly, it all feels like too much. When the psalmist calls us to “sing unto the Lord a new song,” undoubtedly, this is NOT what he had in mind. Yet, how long has it been this way?

Charles Dickens wrote in his 1844 novel, The Life and Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit,

“Change begets change. Nothing propagates so fast.”

Although he was writing about the encompassing societal alterations brought on in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, his words aptly describe the current state of congregational worship and the velocity of change we are experiencing. “The mine which Time has slowly dug beneath familiar objects is sprung in an instant; and what was rock before, becomes but sand and dust.”

“Change begets change.

Nothing propagates so fast.”

For many, there has been a sense the rate of change in our church’s songbooks has increased in recent decades and taken on Dickensian speed, but no study has verified this hunch. This impulse is what motivated the colleagues in this project. As such, we turned to the most obvious source for song information, Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI), and began the process of combing through decades of lists to observe trends.

Early on, we felt like we were staring at a blurred landscape of letters and numbers, titles and dates. In time, though, the data distinctly came into view, as did clear trends and patterns. Like many studies, what we discovered delivered tantalizing answers and myriad new questions and avenues of research.

The Method

CCLI has collected song data from licensed churches since its inception in 1988. Today, the number of yearly audited churches has grown to approximately 10,000 churches (with over 100,000 church license holders, worldwide). CCLI polls a revolving portion of their members every 30 months. From these reports, CCLI creates a bi-annual (every six months) report, representing a listed sampling of the songs sung in various churches. In this study, we retrieved 64 bi-annual Top 100 CCLI lists dating back to CCLI’s beginning.

We decided to organize the Top 100 songs in five-year increments (i.e. 1990-94, 1995-99, 2000-04, 2005-09, 2010-14, and 2015-19) to optimize the identification of important trends.

Early CCLI data, from 1988-94, proved difficult to evaluate and compare. The lifespans of several of the songs in this period predated the launching of CCLI in 1988 [e.g. “I Will Call Upon the Lord” (1981), “Majesty” (1981), and “I Exalt Thee” (1977)]. It seemed most reasonable to start with songs possessing clear start-dates on Top 100 CCLI lists between 1995-99.

With five-year timespans decided, we identified each song that possessed an identifiable four-fold life-curve with a start-date, rise, peak and fall (roughly 75% of the total songs). Characteristically, some songs did not own these traits. Some only identified once or twice on lists [e.g. “Beautiful Things” (2013)]. Others, tornado-like, indiscriminately touched down [e.g. “Be Bold, Be Strong” (1992 through 1997)]. A few songs possessed unusual parabolic growth [e.g. “Lay Me Down” (2013)]. Naturally, too, as we evaluated more recent songs, we observed some song life-curves are still emerging.

With five-year timespans determined and anomalies discarded, we isolated 199 songs possessing clear start-dates, rises, peaks and falls.

The Meaning

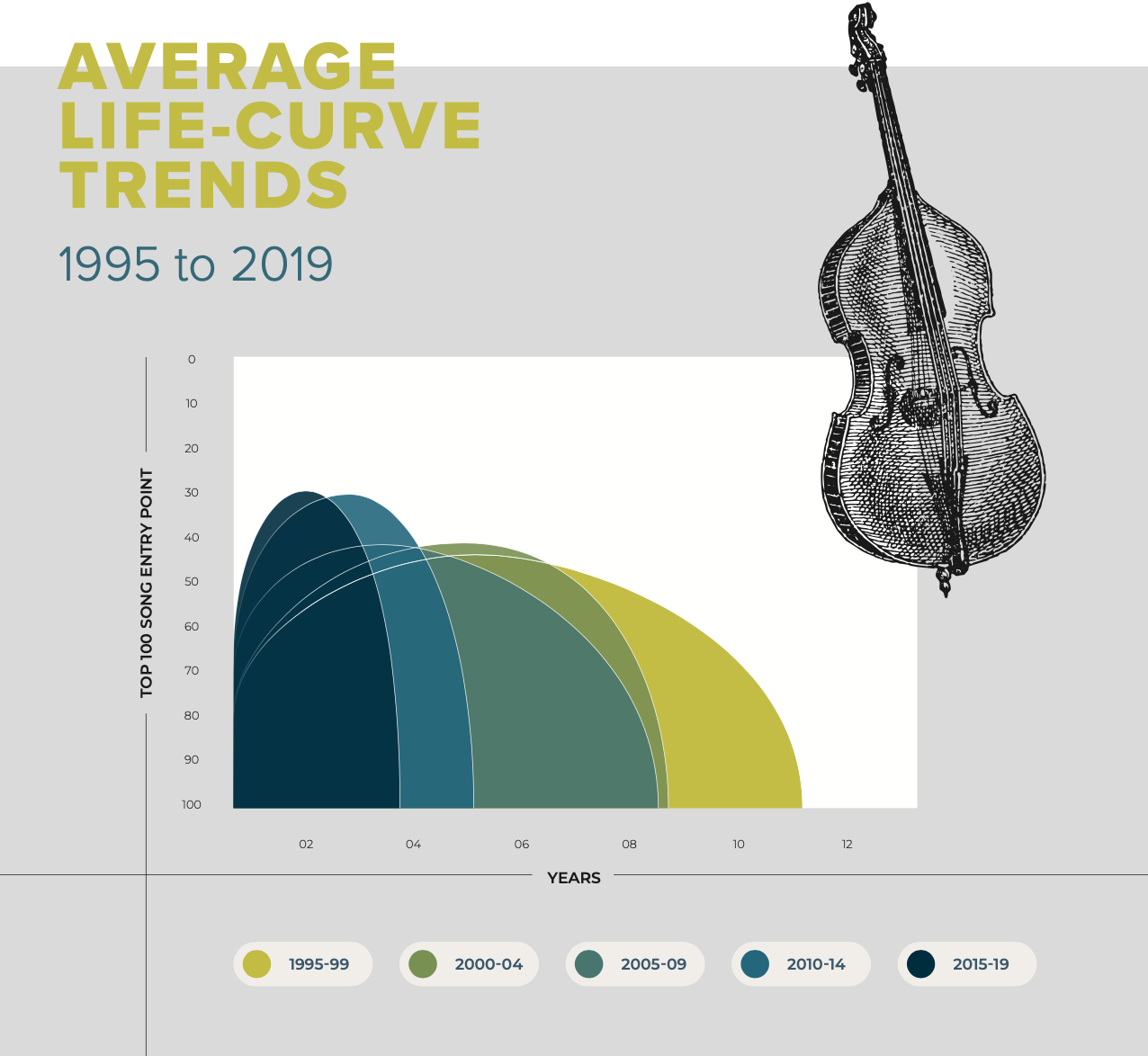

Average Life-Curve Trends (Top 100 songs emerging from 1995-2019)

A clear pattern quickly materialized. The life-curves of the songs, averaged over five-year timespans, increasingly shorten over time (i.e. three times shorter in songs emerging between 1995 and 2019). Collectively, newer songs consist of comparably steeper rises, diminished peaks, and more rapid falls than older songs.

Collectively, newer songs consist of comparably steeper rises, diminished peaks, and more rapid falls than older songs.

While some individual songs in each five-year timespan defy the start-rise-peak-fall pattern of its aggregated curve, many songs in the same span reinforce it. Songs, among many others, fortifying these five-curve trends include:

Graphics, like this, often elicit more questions than answers. Truthfully, one of our project objectives is to prompt a dialogue among curious church leaders.

Graphics, like this, often elicit more questions than answers. Truthfully, one of our project objectives is to prompt a dialogue among curious church leaders.

- What impact has the mode of music production, distribution, and promotion had on these curves?

- How have technological advances and resets (e.g. digital production/distribution, iTunes’ transition to Apple Music, Spotify, Pandora, Facebook, Instagram, etc.) contributed to these song lifespans?

- Are there sociological or cultural conditions at play that might explain what we see?

- What happened between 2005 and 2014 and, more particularly, 2010-2014 to impact such a drastic shortening of the affected song-curves?

- Looking ahead, might there be a “tipping point” in the compression of these curves and, if so, what might it “tip” towards?

A closer look at the results from our study helps address these important questions.

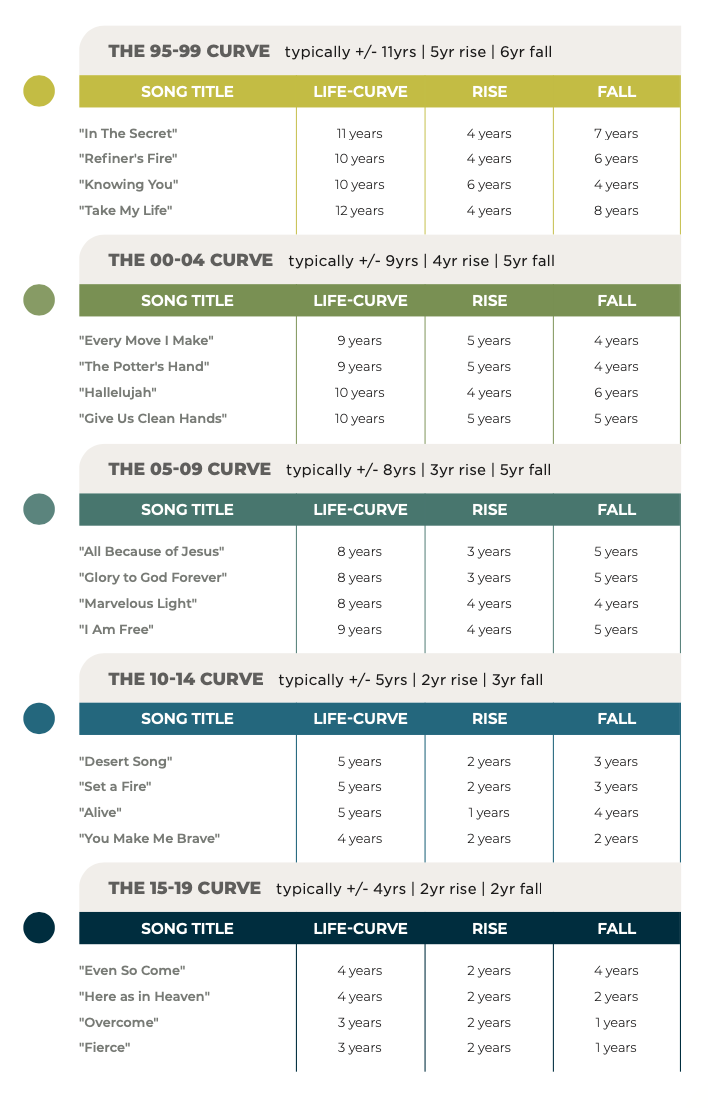

Publication to List Trends (Top 100 songs emerging from 1995-2019)

At some point, it dawned on us there might be important information contributing to the lifespan of songs even before they hit a Top 100 list. Once the five-year song-curves were settled, we asked, “What is the average amount of time between the publication of a typical song and its initial appearance on a CCLI list?” What we discovered was fascinating. Newer songs hit the CCLI lists much faster than older songs. In fact, this gap has lessened by four times in the past 25 years.

Specific songs help to illustrate this. “I Could Sing of Your Love Forever,” for example, was written in 1994, but didn’t appear on a list until April 1999, an approximate five-year span. This gap trend was less for songs written between 2000-2004, evidenced by the song “Give Us Clean Hands” that was published in 2000, but landed on a list, for the first time, in April 2004.

Specific songs help to illustrate this. “I Could Sing of Your Love Forever,” for example, was written in 1994, but didn’t appear on a list until April 1999, an approximate five-year span. This gap trend was less for songs written between 2000-2004, evidenced by the song “Give Us Clean Hands” that was published in 2000, but landed on a list, for the first time, in April 2004.

Around this same time, “I Am Free” was written, but did not appear on a list until 2006. A two-year gap between publication and emergence is illustrated by the 2010 song, “You are Good,” entering in April 2012. In the span between 2015 and 2019, this gap significantly lessened even more. Songs like “Another in the Fire” (written 2018, listed 2019) and “King of Kings” (written 2019, listed 2019) evidence only a small gap between publication and appearance in recent lists.

Once again, questions emerge.

- On the one hand, might this reduced gap empower churches to more easily sing songs that are custom-suited to our times and local or global circumstances?

- On the other hand, might this relatively small gap between publication and listing serve to unevenly advantage songwriters who are already successful?

One thing seems certain. If churches, today, are not likely to introduce a song published more than a year ago (granting exceptions like “Waymaker” released in 2015), then the window for its popularity, across many churches, substantially shrinks.

Entry Point Trends (Top 40 songs emerging from 1995-2019)

Something telling also surfaced from a close look at how and where eventual Top 40 songs enter lists for the first time.

In 1995-1999, songs that eventually became Top 40 songs, entered near the #80 position, then gradually rose in popularity and prominence to Top 40 status (e.g. “Draw Me Close” in at #82 in 1999, peaking at #16 in 2003).

Over the past 25 years, though, Top 40 CCLI songs have tended to enter lists with significantly higher ranking. Today, almost every song that emerges as a popular Top 40 song in our churches enters in or around the #45-#40 position or higher (e.g. In 2020, “We Praise You,” in at #39; “God So Loved,” in at #35; “Battle Belongs,” in at #29; and “Graves into Gardens,” in at #13).

This phenomenon suggests that higher numbers of churches, of presumably varying types and sizes, tend to introduce the same new and popular songs. In previous decades, songs that eventually became Top 40 CCLI songs typically had a cooler initial reception rate.

This phenomenon suggests that higher numbers of churches, of presumably varying types and sizes, tend to introduce the same new and popular songs. In previous decades, songs that eventually became Top 40 CCLI songs typically had a cooler initial reception rate.

It would be interesting to consider a potential correlation between streaming and Christian radio utilization of the list entry points of the most popular songs. The influence of social media, tours, conferences, large stakeholders, and, of course, the impact of COVID on entry point trends would also be intriguing to examine.

One thing, though, is clear. There is evidence popular songs tend to increasingly burst onto the scene in a growing number of churches today.

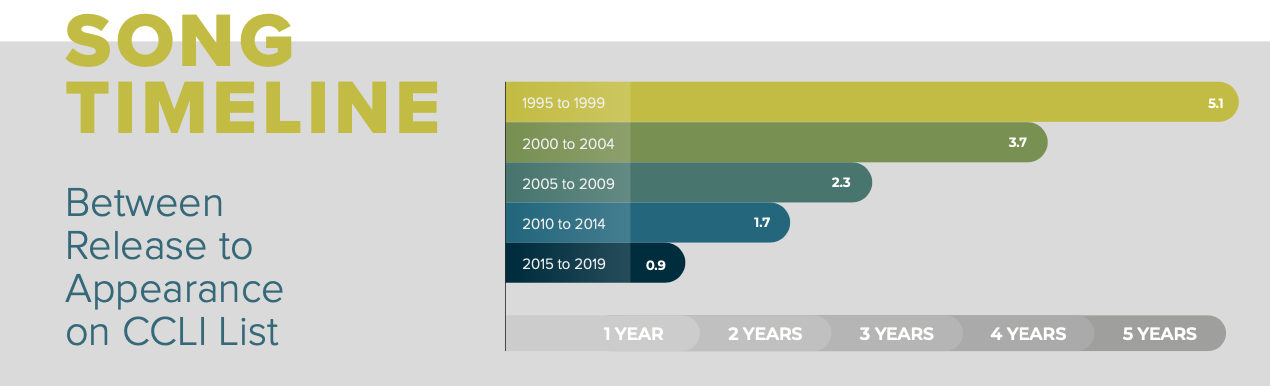

Rise Trends (Top 100 songs emerging from 1995-2019)

As we more closely examined the rise of the songs, some other patterns appeared. The rise rate of change has steadily increased over the past 25 years.

Songs emerging in 2000-2004 rose 22% more quickly than those emerging in churches between 1995-1999. The rate increase for songs entering lists between 2005-2009 was more moderate (15% change in rise increase over the previous period).

A significantly larger rise rate was seen, though, in songs emerging in 2009-2014 (36% change in rise increase over the previous period). And, this rise rate continued to accelerate in 2015-2019 (with an added 23% change in rise increase over the previous period).

The following songs serve as examples of the typical rise trends in each of the five-year timespans.

The following songs serve as examples of the typical rise trends in each of the five-year timespans.

- 1995-99: “I Give You My Heart” (entered 1999), peaked at #16 in 2004

- 2000-04: “My Redeemer Lives” (entered 2001), peaked at #28 in 2004

- 2005-09: “Everlasting God” (entered 2006), peaked at #5 in 2008

- 2010-14: “Here For You” (entered 2012), peaked at #41 in 2014

- 2015-19: “What a Beautiful Name” (entered 2016), peaked at #1 in 2017

Might there be some kind of informational “snowball effect” at play to explain this reality? Do publishers and record labels, radio and other media, churches, and song-reporting gatekeepers all work together, intentionally and otherwise, in a sort of feedback loop?

If this rings true, we might ask if such a trend could indefinitely continue, or if it would hit a “boiling point” (or, more worryingly, a point of disintegration). If these CCLI reporting mechanisms are as ecumenical as we often treat them, there is an argument to be made that we are living in an era with a digital hymnbook, albeit a hymnbook whose page numberings are remarkably fluid and flexible.

Decline Trends (Top 100 songs emerging from 1995-2019)

In direct correlation to rise trends, we discovered songs are declining three times more quickly today than they did 25 years ago. Songs emerging in 2000-2004 fell 23% more steadily than those in 1995-1999.

Fall rates held steady between 2005-2009 (actually expanding slightly by 4% over the previous period) before experiencing a drastic change among songs emerging in the 2010-2014 timespan (43% increase in decline rate over the previous period). This decline trend continued in songs publishing between 2015-2019 (28% increase in decline rate from the preceding period).

…there is an argument to be made that we are living in an era with a digital hymnbook, albeit a hymnbook whose page numberings are remarkably fluid and flexible.

The following songs are prototypes reflecting the decline rate for songs in each of the five-year timespans.

The following songs are prototypes reflecting the decline rate for songs in each of the five-year timespans.

- 1995-1999: “In the Secret” (entered 1999), peaked in 2003, disappeared in 2009

- 2000-2004: “Let Everything that has Breath” (entered 2002), peaked in 2004, disappeared in 2008

- 2005-2009: “Marvelous Light” (entered 2006), peaked in 2009, disappeared in 2013

- 2010-2014: “Broken Vessels” (entered 2014), peaked in 2017, disappeared in 2019

- 2015-2019: “Overcome” (entered 2018), peaked in 2018, disappeared in 2019

Are songs falling and disappearing from the lists faster to make room for new songs (a “displacement” theory) or because they oversaturate the culture (a “dissatisfaction” theory)? Could it be neither? Could it be both? Could the speedier disappearance of songs have to do with increasing isomorphism in style, performance, and structure leading to boredom? Has congregational worship evolved into a form of addiction that requires new—and more—stimulation to satisfy and/or keep the worshiper’s focus? If so, might there be unforeseen consequences, be they positive or negative, to such a reality?

Perhaps a way forward is to explore ways to ensure these resources remain tools we use, not tools that use us.

The Mobilizing

What shall we say, then? If more and more churches are singing the same songs, isn’t that a good thing? If they’re singing those songs for shorter and shorter seasons, though, is that a good thing? As with all things this side of eternity, the trends we’ve just reviewed are a mixed-bag of sorts.The same hypothetical worship leader from our opening section—our modern day Martin Chuzzelwit, the one who felt overwhelmed by the current rate of change—might have felt woefully under-resourced 25 years ago. Today, we have instantaneous access to songs about almost anything, in virtually any style imaginable, written and sung by worship artists around the world. We also have resources to help us sift through the rising tide to identify the particular songs that seem to be resonating around the world for diverse curators of worship. Perhaps a way forward is to explore ways to ensure these resources remain tools we use, not tools that use us. The Church will always want to join the psalmist in singing those “new songs,” while ensuring its worship is as firm, grounded, and familiar as the Psalter, itself.

This study was completed by:

- Marc Jolicoeur: pastor, Moncton Wesleyan Church

- Mike Tapper: religion chair, Southern Wesleyan University

- Lisa Corbin: research director, Southern Wesleyan University

- Charldon Dennis: mathematician, D.W. Daniel High School

- Andrea Hunter: songwriter/editor, Worship Leader magazine

- Jessica Lucas: graphic design, Flo Design Co.

Want to hear our reaction to this study? Click here

What's Your Reaction?

Over the last 30 years, Worship Leader Magazine has been blessed to have many different contributors on the editorial team - this is their archive.