10 Ways to Communicate Well in Today’s Visual Culture

Youth ministry leader Mike Yaconelli found out only a few minutes in advance that the group he was about to address was made up of postmasters rather than toastmasters. What did he do? Stay tuned.

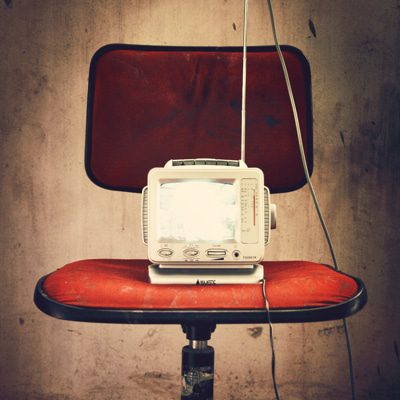

Great communication is about knowing the audience and the culture. Today, our communication occurs within a highly visual culture, from magazines, movies, fashion, and billboards to TV, YouTube, and selfies. How can we communicate well in the midst of this sea of images?

- Embrace iconoclasm.

The attractive personas that dominate the news, stage, and screen often fall from glory. Celebs recycle with tales of excess—aided by the paparazzi. Company logos bite back when organizations are caught mistreating employees, customers, and stakeholders. Churches struggle to keep afloat with iconic ministers amidst waves of social-media gossip and congregational backbiting and disaffection. Seek iconicity at your own peril. Be winsomely iconoclastic—a genuine person without airs.

- Seek substance on the edges of vogue style.

Think of visual style as multimedia fashion. How we look, talk, and text—and the technologies we use in front of others—are powerful messages. Even being out of fashion can become a matter of bohemian or hipster trendiness. I wear bow ties. You can laugh at my unstylishness or ponder my ambiguity—hopefully the latter. If people don’t immediately typecast me, I have a chance of getting a message across without merely preaching to the choir of those who are similarly outfitted. The lesson is to live slightly off visual kilter, however you can pull it off. Substance sticks out its nose at the frayed edges of style. Communicate on the visual borders.

- Carry a grateful countenance.

A while back I was stuck in line at a phone store with a mob of discontented smart phone users. Forty minutes and counting. Everyone was hopping mad. Then I noticed that the walls were plastered with posters of super-smiling cell users. I pointed out to the real estate agent next to me (we had time to get personal) the contradiction between the faces on the glitzy posters and the falling countenances of customers. We howled. Others joined in. Suddenly the faces of the impatient crowd were unified in a kind of anti-technological worship event, a humble challenge to technological hubris. There is nothing like a genuine smile to cut through everyday nonsense. When we authentically wear our grateful hearts on our faces, we invite others to read the hopeful messages.

- Listen beyond the stereotypes.

The age of cultural diversity is also the era of visual stereotypes. We try to make sense of optical complexity by using narrow categories of interpretation. We catalog each other by race, ethnicity, social class, and other popular simplicities. We even join churches composed of similar-looking people. Real diversity is personal, based on life experience. We challenge stereotypes by listening to our diverse narratives and then loving each other as distinct persons. Love begins with listening and is never abstract.

- Transcend generational bubbles.

Today’s visual culture is media rich but generationally divided. Each generation—even between siblings—tends to consume it’s own visual media. When we look at others, or at ourselves in a mirror, we see a generation. Body sculpting changes our image but not our generational mindset. Learning to commune across generations is perhaps the most challenging ministry issue of our time. Try watching movies that please your children, parents, or the elderly couple you see weekly in the pew behind you—and talk with them about the experience.

- Handcraft personal notes.

Computer text is visually impersonal no matter how we try to embellish it with emoticons and stylistic flair. By contrast, your handwriting says that you personally care enough to invest time and thoughtfulness in a relationship. Buy some personalized note cards and envelopes. Send one a day to someone who has served you. Avoid stock greeting cards unless the words are truly what you would write; even then, add a handwritten note.

- Question initial impressions.

In our visual culture, we quickly get turned on and off by people just based on immediate impressions. We surf others’ images without considering that we might be badly mistaken. You can see this at work in post-worship conversations as congregants gravitate away from those who look unusual. Lew Vander Meer says in Recovering From Churchism that this problem of first impressions is perhaps the major reason that many churches don’t grow. Christian hospitality calls us to make room in our minds and hearts—not just in our homes—for those who appear to be different than us. When we first see others as God’s image bearers, we begin our communication with gratitude, respect, and wonder.

- Seek communicative wisdom.

Every year hundreds of new books claim to offer the communication skills we need to be successful. Publishers call communication an “evergreen” topic. The book titles and covers are enchanting. But the content is almost always the same old tips and tricks. Contrast such books with this bit of monastic wisdom: “Speak only if you can improve upon the silence.” Or this one: “Listen with your heart.” Or this one: “Communicate with others the way you would want them to communicate with you.” One of my favorites is from Augustine: The purpose of public speaking is to “love your audience as your neighbor.” In fact, that insight led me to craft a short book titled An Essential Guide to Public Speaking: Serving Your Audience With Faith, Skill, and Virtue. Modern, mediated visual culture emphasizes how to influence people, not how to serve them. Keep an ongoing list of wise communication practices and review it regularly. Start by reading the Book of James. Tape on your computer screen or keyboard a small note with the three most important bits of communicative wisdom on it.

- Embrace others’ honest doubts.

This essential point deserves a separate article, but I’d like to try to dissect it briefly. Visual culture has more to do with impressions and affect than with narrow logic or reason. People are more likely in image-oriented cultures to come to faith initially by a kind of intuition about God’s love than by arguments in favor of God’s existence. One result is that “visual believers” are more likely to hold faith and doubt simultaneously—or at least to be more open with close friends about their doubts. Doubt for many people is not so much a stumbling block to faith as the context for their faith. They are open to the love of God and to grace, but not so much to strident dogmatism. They are seeking love and to become God’s beloved. They often begin to experience such love when believers spaciously accept and affirm them, doubts and all. Others’ true (or “honest”) doubt is one of the greatest assets for faithful communicators in our age.

- Be an amateur.

Communicate for the love of it—and for the love of others. Excess polish makes our communication less authentic. The preacher who slips up now and again and can laugh along with the congregation will be more beloved than the one who practices pristine elocution. Students love fittingly self-effacing teachers. Besides, few of us can compete with personas crafted by cutting-edge video and audio editors. We are who we are, foibles and all.

So what did Yaconelli do when faced with an audience of postmasters rather than toastmasters? He didn’t pretend to have anything prepared for the group. He didn’t rely on great rhetoric or performance abilities. Instead he simply and honestly talked about something that everyone experiences.

As Yaconelli recalled,

On my way up to the podium I decided to talk about something I frequently talk about: the loss of passion. It was one of the most rewarding experiences I ever had. Halfway through my talk, people were crying throughout the audience. When I was done, they rose to their feet to underscore my call to rediscover passion. They were expecting a lecture on stamp regulations, and I was expecting to talk about using voice inflection and gestures, but just under the surface, a group of postmasters got in touch with their longings for passion again.

Yaconelli loved those postmasters as his neighbors. Without PowerPoint or video, but with an iconoclastic presence and a grateful countenance, he addressed them as real persons, not as first impressions or stereotypes. He got to the heart of something that really mattered to them and to him. Visual culture provides amazing opportunities for heart-to-heart connection among authentic people.

Quentin J. Schultze is a communication professor, writer, speaker, mentor, and consultant. He founded the “art of servant communication.” He earned a PhD from the Institute of Communications Research at the University of Illinois and eventually joined the faculty at Calvin College (Grand Rapids, MI), where he is the Arthur H. DeKruyter Chair and a Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences. You can follow his updates by subscribing to his blog or Tweets (@quentinschultze).